浏览多年,不见国内文献有令人信服的解释,只好自己动笔写这篇文章。标题是三个关键词,它们的展开,就是理论。例如,“心理类型”,《荣格全集》普林斯顿大学出版社英译二十卷本的第六卷,不仅以此为标题,而且要铺叙若干其它卷章才可理解这一卷的全部内容。也因此,这套“荣格全集”(可检索)是我最常用的工具书。此处“最常用的”,对我而言,就是最需要反复琢磨的。例如第九卷第I部分,“原型与集体无意识”,从我读博士期间开始计算,已读了三十多年,以致于现在,我反复琢磨,将“archetypes”译为“原型”是否正确(我最初是将它译为“考古类型”的)。

第一个关键词,“character”,仅就希腊语词“ethos”这一常见的英译而言,勉强译为“性格”(这是因为“气质”或“性情”已被我们的日常语言严重污染了)。关键是,赫拉克利特残篇,“Ηθος Ανθρωπος Δαιμων”(ethos anthropos daimon),常见的英译是,“character is fate”,民国以来,这句话常被译为“性格即命运”。

周辅成,1954,《西方伦理学名著选辑》上卷,第1章第1节,“赫拉克利特”,第(一)段,“论命运对于人的意义”,……命运就是必然性——他宣称命运的本质就是那贯穿宇宙实体的“逻各斯”。〔《著作残篇》,123〕人的性格,就是他的命运。

克劳斯•黑尔德《世界现象学》,孙周兴编,倪梁康等译,北京三联书店版,第12页,主张译为:“人的习性就是他的守护神灵。”出现在这里的全文是:这个对自身负责所做的决定或许最清楚地表露在赫拉克利特的一个箴言中:人的习性就是他的守护神灵。“习性”(Ethos)在这里是指生活的自身负责的持续状况。“神灵”(daimon)则是对那个出现在生活的幸与不幸之中的、无法支配的巨大力量的传统称呼。赫拉克利特的箴言可以说是把这个“神灵”世俗化了。这个箴言——与海德格尔的解释相反——重点应当在第一个词,它意味着:生活的幸与不幸取决于“习性”。 由此可见,我们不应简单地将“ethos”译为“性格”,因为它还有诸如“习俗”这样的涵义。因此,“习性”是一个合适的语词。一方面,习性表达了习俗对性格的熏染过程。另一方面,习性表达了性格对习俗的独立。这样的双重表达,意味着“性格的悖论”。恰如荣格心理学在美国的掌门人希尔曼(James Hillman)为2001年出版的希腊文与英文对照《赫拉克利特残篇》(Fragments: the Collected Wisdom of Heraclitus translated by Brooks Haxton)所写“前言”的标题:“I am as I am not”(我是恰如我不是)。这一标题,出自赫拉克利特残篇。容我全文转录希尔曼的文字(引文里的数字是赫拉克利特残篇里句子的编号):You can, however, reflect your own mind, see into your own thoughts. You can become psychological or, as he puts it, “Applicants for wisdom do what I have done: inquire within” (80). “People ought to know themselves” (106). This psychological turn means you cannot know the psyche no matter how endless your search (71), since consciousness is always also its opposite, unconsciousness. How better say this than: “I am as I am not” (81)。我的译文:你能够,毕竟,反观自心,看入你自己的思想。你能够变成心理学的,或如赫拉克利特所言,“运用智慧的人们,请照着我已经做过的这样做:向内探索”(残篇80)。“人们应当认识他们自己”(残篇106)。这一心理学转变意味着你无论怎样无穷尽地探索也不能认识心理(残篇71),因为意识总也是与它对立的无意识。最佳的表达就是:“我是恰如我不是”(残篇81)。

荣格心理学的方法论特征,是我们熟悉的“对立统一规律”,尤其是他晚期的著作《荣格全集》第十四卷。我检索《荣格全集》,“Hegel”总共出现18次。不过,根据此刻屏幕宽度显示的荣格全集总共七千多页。尽管如此,荣格很熟悉黑格尔的“正题-反题-合题”辩证原理。检索“dialectical”(辩证的)总共出现75次,同样的屏幕宽度。

我们很容易根据常识来想象一个人的习性养成过程,从他带着先天因素投胎开始。不过,我更喜欢的模型,称为“双重历史性的燕尾模型”,源自海勒女士的著作《普适伦理学》(Agnes Heller,1988,《General Ethics》)第一章“人之条件”(也许因为海勒女士1986年担任纽约“新社会研究”学院的“阿伦特讲座”教授故而采纳阿伦特名著《人之条件》为第一章标题),原文值得录译:Each person is thrown into a particular society by the accident of birth. The conception of a particular personal a priori via an individual's progenitors is in itself an accident. It is also an accident that this person is thrown into this or that particular social a priori. There is nothing in the genetic make-up of an embryo that would predestine its 'being thrown' into any particular social a priori; it is only predestined to be thrown into a social a priori. Destiny as accident is thus twofold. Transforming this accident into determination and self-determination is precisely what 'growing up in a particular world' is all about. I term this 'dovetailing' of the two a priori ‘historicity’,我的译文:每一个人由于出生偶然被抛入一个特定社会。特定个人经由先祖投胎自成一种先天偶然性。这一特定个人被抛入这一个或那一个特定的社会又成另一种先天偶然性。在一个胚胎的基因构成中没有任何事情可预定其被“抛入”任一特定社会的先天性;唯一先天预定的命运就是它被抛入某一社会。命运之为偶然于是成为双重的。将这一偶然转换为决定性和自我决定性刚好就是“在特定世界里成长”这一短语的全部涵义。我称之为双重先天“历史性”之“燕尾”模型。

接着的这一段,是燕尾模型的解释。容我继续录译:…… while nothing is 'written' or coded into the personal genetic a priori which would predestine anyone for one particular social a priori, not all personal genetic a priori fit equally, or equally well, into a particular social a priori. If a hundred infants are born into the same social a priori, it is obvious that some will find it more difficult, and others will find it easier, to fit into the same social a priori. 我的译文:……尽管在个人的基因里没有任何编码先天预定其适合任一特定社会,但并非全体个人的基因平等地先天适合于某一特定社会。若一百名婴儿先天预定出生于同一社会,显然,先天地,一些婴儿更难以适应而另一些婴儿更容易适应。

我常用两条可想象的正态分布曲线来解释海勒的“双重历史性”。第一条正态分布曲线由全体人类基因型构成,在这条曲线上,先天地,一个人的基因型对应于一个特定的点。第二条分布曲线由全体人类社会形态构成,在这条曲线上,一个社会形态对应于一个特定的点。显然,一个人的基因型(genotype)被抛入于一个特定社会之后形成的表型(phenotype)与该社会形态之间有完美配合的概率极小,以致可以忽略。

海勒在这部对我产生长期影响的著作开篇,阐述了任何“道德理论”都具备的三重特质:1)解释性,2)规范性,3)疗愈性。

以往基于“人性不变”假设的传统理论,大多强调规范性。不过,斯多亚学派的道德理论特重“疗愈性”,而诸如社会博弈论这样的道德理论则偏重于“解释性”。海勒的“燕尾模型”,当然是解释性的。

回到燕尾模型,在燕尾交叉点,一个人被抛入于特定的社会,他于是必须面对他的“双重历史性”。又因为先天因素使他不能完全适应特定的社会,他可能有三条演化路径,1)将社会规范内置于自我意识,从而抑制任何违背社会规范的欲念。于是这些欲念沉入荣格所说的“无意识”或弗洛伊德所说的“潜意识”,它们当然还可有机会涌现为“意识”或导致心理障碍;2)心理异常,所谓“心理变态”(参阅《变态心理学》标准教材提供的定义),美国精神病学会最新发布的第五版《精神疾病诊断与统计手册》(“DSM-5”被评论为“不可靠的”、“非科学的”、“毫无意义的”)定义的“精神分裂症谱系”,从“人格转换障碍”到“精神分裂症”;3)创造价值,获得社会的承认。

上列三种演化路径,既有解释性又有疗愈性。有许多天才人物在尚未被社会扼杀的时候,创造价值获得了社会的承认。不难想象,有更多的天才人物被社会扼杀了,在他们有机会创造价值并获得社会承认之前。当然,也有少数天才人物被抛入于“上流社会”得以充分开发自己的禀赋。我的《行为社会科学基本问题》(上海人民出版社2017年)充分阐述了海勒的“双重历史性”并提出了“行为社会科学”的基本问题。

一个人的习性就是他的守护神灵(“性格即命运”),这里的“习性”(性格),是上述三种演化路径的后果,而且往往是这三种后果的混合。在这样的阐释之后,我可以略为放心地使用“性格”这一语词。不过,我仍要补充一段荣格的文字,《荣格全集》第七卷第243节:Fundamentally the persona is nothing real: it is a compromise between individual and society as to what a man should appear to be. He takes a name, earns a title, exercises a function, he is this or that. In a certain sense all this is real, yet in relation to the essential individuality of the person concerned it is only a secondary reality, a compromise formation, in making which others often have a greater share than he. 我的译文:面具(persona)根本而言毫无真实可言:它是个体与社会之间的妥协从而使一个人显现为应当的样式。他有一个名字,获取一个头衔,履行一种功能,他是这个或那个。在某种意义上说所有这些只是派生的真实性,形成于一种妥协,从而其他人常常比他拥有更大份额。

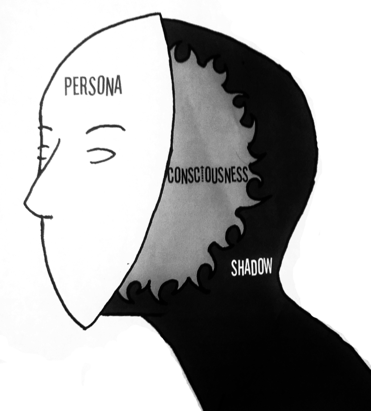

荣格此处引入的术语“persona”,拉丁文的意思是“假面”。社会生活,犹如假面舞会。不过,“原始人”(archaic man)的意识尚未凸显为“自我”意识,因此,原始人没有假面。仅当“意识”(consciousness)凸显为“自我意识”(ego)之后,为适应特定的社会,它必须戴上“假面”(mask)。同时,自我意识也有了“暗影”(shadow)——那里隐藏着被自我意识拒绝承认的全部欲念,如图1所示。

图1. 自我意识的假面与暗影。

我继续录译荣格的文字,《荣格全集》第三卷第438节:When we speak of a thing being “unconscious,” we must not forget that from the standpoint of the functioning of the brain it may be unconscious to us in two ways—physiologically and psychologically. I shall discuss the subject only from the latter point of view. For our purpose we may define the unconscious as the sum of all those psychic events which are not apperceived, and so are unconscious. 我的译文:当我们说一件事是“无意识的”时候,我们必不忘记从脑功能的视角有两种意义的无意识——生理学意义的和心理学意义的。我仅在心理学意义上讨论这一主题。为此目的我们可以定义无意识为全部不被觉察的,从而是无意识的心理事件。

《荣格全集》第三卷第439节:The unconscious contains all those psychic events which do not possess sufficient intensity of functioning to cross the threshold dividing the conscious from the unconscious. They remain, in effect, below the surface of consciousness, and flit by in subliminal form. 我的译文:无意识包含不占有足以超过意识与无意识之间分界阈值的功能紧张性的全部心理事件。这些心理事件保持,有效地,在意识的表面之下,并以潜意识的形式掠过。

以上两段文字,荣格写于1914年(他开始制作“红书”),早于荣格思想的“成熟期”(大约1920年至1930年)。那时,荣格与弗洛伊德的决裂激发荣格全面地转向集体无意识的探索,而这一探索十分漫长。参阅荣格1920年为《心理类型》(即《荣格全集》第六卷)撰写的瑞士第1版序言,以及1929年的评论“弗洛伊德与荣格——冲突”(《荣格全集》第四卷第768节至784节)。

有鉴于此,我引述长期主持苏黎世荣格学院的法兰茨博士(她年轻时帮助荣格翻译并勘定希腊文和拉丁文的资料)的几本晚期著作:(1)Marie-Louise von Franz,1974,《Archetypal Patterns in Fairy Tales》(童话里原型的模式)。这本书是法兰茨1974年在苏黎世荣格学院的授课文稿,第1讲里有一个提醒:You must never forget that Jung built up his concepts of shadow, animus and anima, and Self from looking at the single individual an individual Mr. Meier or a Mrs. Miller experiencing the unconscious. 我的译文:你们绝不要忘记荣格基于他对梅尔先生的个案分析和对米勒小姐的个案分析建构了他的概念“暗影”、“阿尼姆斯和阿尼玛”、以及“原我”——周党伟将荣格的概念“Self”译为“原我”,似乎比通常译为“自性”或我自己使用的译名“大我”更恰当。检索《荣格全集》可知,荣格在第五卷(《转化的象征》)感谢法兰茨博士帮助翻译和校勘希腊文和拉丁文资料。第五卷第I部分第3章,是米勒小姐的案例分析。

现在,(2)我引用法兰茨的另一部晚期作品:Marie-Louise von Franz,1974,《Shadow and Evil in Fairy Tales》(童话里的暗影与邪恶)。这本书的第一部分是法兰茨1957年在苏黎世荣格学院的演讲,开篇是这样写的:THE PSYCHOLOGICAL DEFINITION of the shadow, which we must bear in mind before going into our material, can vary greatly and is not as simple as we generally assume. In Jungian psychology, we generally define the shadow as the personification of certain aspects of the unconscious personality, which could be added to the ego complex but which, for various reasons, are not. We might therefore say that the shadow is the dark, unlived, and repressed side of the ego complex, but this is only partly true. Jung, who hated it when his pupils were too literal-minded and clung to his concepts and made a system out of them and quoted him without knowing exactly what they were saying, once in a discussion threw all this over and said, “This is all nonsense! The shadow is simply the whole unconscious.” He said that we had forgotten how these things had been discovered and how they were experienced by the individual, and that it was necessary always to think of the condition of the analysand at the moment. If someone who knows nothing about psychology comes to an analytical hour and you try to explain that there are certain processes at the back of the mind of which people are not aware, that is the shadow to them. 我的译文:在进入主题之前我们必须记在心里,暗影的心理学定义可以有很大的差异而且不像我们通常假设的那样简单。在荣格心理学里,我们通常定义暗影为无意识人格特定属性的人格化,这些属性可以,但出于各种理由而没有附加于“自我情结”(ego complex)。我们或许因此声称暗影是阴暗的,无生机的,并且是自我情结之受到压抑的方面,但这只是部分的真相。荣格非常不喜欢他的学生们心智过分局限于字面涵义从而紧抓他的概念并据此建构体系而且引用他的话语却不知道他们在说什么,有一次他在讨论中抛出了全部这些批评并说“都是胡言乱语!简单而言暗影就是全部无意识。”他说我们已忘记了这些内容是怎样被发现的以及它们是怎样被个体经验的,并且必须总是想到被分析者当下的情境。如果有一个对心理学一无所知的人来做心理分析而你试图解释在心智背后有一些人们毫无觉察的过程,对他们而言那就是暗影。

法兰茨的概括:So in the first stage of approach to the unconscious, the shadow is simply a “mythological” name for all that within me about which I cannot directly know. 我的译文:所以在接近无意识的第一阶段,暗影简单而言就是在我内部而我不能直接认识的全部内容的一个“神话的”名称。

继续引述法兰茨的开篇:Only when we start to dig into this shadow sphere of the personality and to investigate the different aspects, does there, after a time, appear in the dreams a personification of the unconscious, of the same sex as the dreamer. But then this person will discover that there is in this unknown area still another cluster of reactions called the anima (or the animus), which represents feelings, moods, and ideas, etc.; and we also speak of the concept of the Self. For practical purposes, Jung has not found it necessary to go beyond these three steps. 我的译文:仅当我们开始探索人格的暗影球面并研究其不同性质时,在一段时间之后,无意识的人格化才出现在梦中,与梦者性别相同。但是随后这个人将发现在这一未知领域还存在另一团反应,被称为“阿尼玛”(或“阿尼姆斯”),它们代表感受,心绪,以及意念等等;并且我们也谈论“原我”这一概念。对实践目的而言,荣格认为没有必要超出这样三个步骤。

最后,(3)我抄录法兰茨《童话的解释》(Marie-Louise Von Franz,1970,《The Interpretation of Fairy Tales》)最后一章的开篇文字:Though nearly all fairy tales ultimately circle around the symbol of the Self or are “ordered” by it, we also find in many stories motifs which remind us of Jung’s concepts of the shadow, animus, and anima. In this chapter I will give the interpretation of an example of each of these motifs. But we must again realize that we are dealing with the objective, impersonal substructure of the human psyche and not with its personal individual aspects. The figure of the shadow in itself belongs partly to the personal unconscious and partly to the collective unconscious. In fairy tales only the collective aspect can occur—the shadow of the hero, for instance. 我的译文:尽管几乎全部童话故事最终围绕“原我”这一符号展开或被“原我”安排为有序的,我们仍发现许多故事的主题让我们想到荣格的概念“暗影”、“阿尼姆斯”、“阿尼玛”。在这一章我将为这些主题各提供一个案例解释。但是我们必须再次意识到我们正在处理的对象,人类心理非私人的子结构并且不带有私人的个体性质。暗影的意象本身部分地属于个体无意识部分地属于集体无意识。在童话里仅集体性质能够发生——例如,英雄的暗影。

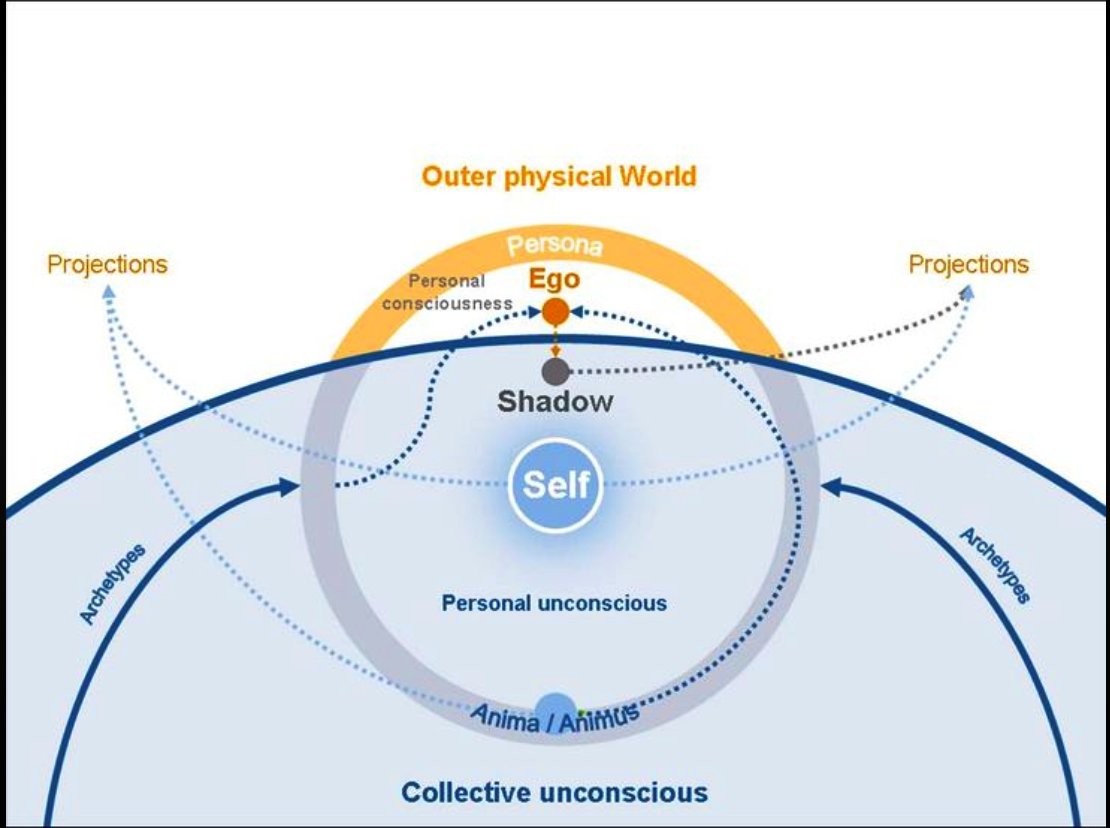

在上述全部引文之后,图2也许有助于理解原我与暗影在无意识领域里的位置。注意,图2的缺陷是囿于静态。自我意识与原我的关系本质上是一个演化过程。我用“暗夜执烛”来譬喻自我意识(烛光)在广袤的无意识领域内的探索以及“原我”随这一探索而演化的过程。

图2. 自我意识(ego)、暗影(shadow)、原我(Self)。

我的补充说明:(1)Self可包含ego及其shadow,但此处Self仅由一个“原型”来表达;(2)Self可与集体无意识相通,但此处Self被“个体无意识”包围,从而与集体无意识完全分离。

此外,我应列出图2使用的其它术语:假面(persona)、原型(archetypes)、“个体意识”(personal consciousness)、“投射”或“心理投射”(projections)、“个体无意识”(personal unconscious)、“阿尼玛/阿尼姆斯”(anima/animus)、“外部的物理世界”(outer physical world)、“集体无意识”(collective unconscious)。

尽管有图2借鉴,我还是要牢记希尔曼的警告,尽量不讨论“原我”这一概念:I have also tried to prevent the most pernicious term of all, “self”, from creeping into my paragraphs. This word has a big mouth. It could have swallowed into its capacious limitlessness and without a trace all the more specific personifications such as “genius”, “angel”, “daemon”, and “fate”. 引文出自 James Hillman,1996,《The Soul’s Code:In Search of Character and Calling》 (灵魂密码:寻找性格与神召)。我的译文:我还尝试避免让这些术语当中最邪恶的“原我”潜入我这本书的段落里。这个单词有一张大嘴。它可以广袤无垠而且不留痕迹地吞噬全部更特殊的人格化表达诸如“天才”(拉丁语里男性的“守护神”)、“天使”、“神灵”、“命运”。

荣格关于“冷战”时代人类命运的思考,成为他生前最后一部著作的主题,1957年出版,《未发现的自我》(The Undiscovered Self with Symbols and Interpretation of Dreams),英译本第I编“未发现的自我”取自《荣格全集》第十卷,英译本第II编“梦的解释与象征”取自《荣格全集》第十八卷。

我抄录第I编第527节(选自第4章“个体对他自己的理解”):In the same way that our picture of the world had to be freed by Copernicus from the prejudice of geocentricity, the most strenuous efforts of a well-nigh revolutionary nature were needed to free psychology, first from the spell of mythological ideas, and then from the prejudice that the psyche is, on the one hand, a mere epiphenomenon of a biochemical process in the brain and, on the other hand, a purely personal matter. The connection with the brain does not in itself prove that the psyche is an epiphenomenon, a secondary function causally dependent on biochemical processes in the physical substrate. Nevertheless, we know only too well how much the psychic function can be disturbed by verifiable processes in the brain, and this fact is so impressive that the subsidiary nature of the psyche seems an almost unavoidable inference. The phenomena of parapsychology, however, warn us to be careful, for they point to a relativization of space and time through psychic factors which casts doubt on our naïve and overhasty explanation in terms of psychophysical parallelism. For the sake of this explanation people deny the findings of parapsychology outright, either for philosophical reasons or from intellectual laziness. This can hardly be considered a scientifically responsible attitude, even though it is a popular way out of a quite extraordinary intellectual difficulty. To assess the psychic phenomenon, we have to take account of all the other phenomena that go with it, and accordingly we can no longer practice any psychology that ignores the existence of the unconscious or of parapsychology. 我的译文:以与哥白尼将我们的世界图景从地球中心主义解放的同样方式,需要一种实质上几乎是革命性的奋发努力来解放心理学,首先从神话观念的魔咒,其次从这样一种偏见——它一方面认为心理只不过是脑内生物化学过程的附加现象,另一方面认为心理纯粹是个人事务。与脑的联系本身不能证明心理是一种附加现象,一种偶然依赖于物理基底生化过程的次级功能。毕竟,我们特别知道心理功能怎样受到可检测的脑内过程干扰,我们对这一事实如此印象深刻以致心理的从属性的实质似乎是不可避免的推论。尽管,超心理学(灵学)现象提醒我们要谨慎,因为这些现象意味着空间与时间通过心理因素而被相对化从而对我们天真和鲁莽的“心理-物理”平行论解释投下怀疑。出于这种平行论的解释,人们从一开始就拒绝灵学,要么因为哲学的理由要么因为智性的懒惰。这一情形很难被认为是科学地负责的态度,尽管它是摆脱极端智性困难的一种普遍方式。为了接近心理现象,我们必须考察与心理相关的全部其它现象,据此我们不能再实践任何无视灵学或无意识现象的心理学。

荣格《未发现的自我》第I编第五章的结语是这样的(第564节):Here each of us must ask: Have I any religious experience and immediate relation to God, and hence that certainty which will keep me, as an individual, from dissolving in the crowd? 我的译文:这里我们每一个人必须询问:我是否有任何宗教体验并与神直接关联,从而这种确定性将使我,这一个人,从乌合之众当中分离出来?

然后,荣格在这本书第I编第六章开篇为上面的问题提供了一个简要回答(第575节):To this question there is a positive answer only when the individual is willing to fulfill the demands of rigorous self-examination and self-knowledge. If he does this, he will not only discover some important truths about himself but will also have gained a psychological advantage: he will have succeeded in deeming himself worthy of serious attention and sympathetic interest. He will have set his hand, as it were, to a declaration of his own human dignity and taken the first step towards the foundations of his consciousness—that is, towards the unconscious, the only available source of religious experience. This is certainly not to say that what we call the unconscious is identical with God or is set up in his place. It is simply the medium from which religious experience seems to flow. As to what the further cause of such experience may be, the answer to this lies beyond the range of human knowledge. Knowledge of God is a transcendental problem. 我的译文:仅当一个人愿意满足自我省察和自我认知的严格要求时才对上面的问题有一个正面解答。假如他这样做,他将不仅发现关于自己的一些重要真相而且将获得一项心理学优势:他将认为自己配得上严肃的关注与同情的兴趣。他将放下他的手,恰如他已做的那样,做一项他自己的人的尊严宣言并向着他的意识之基础——也就是,无意识,宗教体验的唯一可用源泉,迈出第一步。这肯定不是说我们所谓的无意识是与神同一的或能确立这样的地位。简单而言无意识只是宗教体验涌流的中介。至于这些宗教体验有什么更进一步的可能原因,答案超出了人类知识范围。关于神的知识是一个超验问题。

在《寻求灵魂的现代人》(C. G. Jung,1933,《Modern Man in Search of a Soul》)第七章“原始人”接近结尾部分,荣格提出了一个意味深远的猜测:does the psychic in general—that is, the spirit, or the unconscious—arise in us; or is the psyche, in the early stages of consciousness, actually outside us in the form of arbitrary powers with intentions of their own, and does it gradually come to take its place within us in the course of psychic development? Were the dissociated psychic contents—to use our modern terms—ever parts of the psyches of individuals, or were they rather from the beginning psychic entities existing in themselves according to the primitive view as ghosts, ancestral spirits and the like? Were they only by degrees embodied by man in the course of development, so that they gradually constituted in him that world which we now call the psyche? This whole idea strikes us as dangerously paradoxical, and yet we are able to conceive something of the kind. Not only the religious teacher, but the pedagogue as well, assumes that it is possible to implant in the human psyche something that was not previously there. The power of suggestion and influence is a fact; even the most modern behaviorism expects far-reaching results from this quarter. The idea of a complicated building-up of the psyche is expressed in primitive form in many widespread beliefs—for instance, possession, the incarnation of ancestral spirits, the immigration of souls, and so forth. 我的译文:是否心理一般而言——也就是说,精神,或无意识——从我们内心发生;抑或,在意识的早期阶段,精神其实以任意形式的力量外在于我们的心灵并带着它们自己的意向,这种外在力量随着心理的发育逐渐在我们内心植根?是否这些与我们心灵分离的心理内容——用我们的现代语言表述——从未成为个体心理的成份,抑或如原始人想象中诸如幽灵和祖先精神那样最初就存在着自为的心理实体?是否这些心理实体在发育过程中仅仅是部分地植入于人的内心,从而它们逐渐在人的内心构成了我们现在称为心理的世界?这一观念整体击中我们,危险地具有悖论性质,而我们尚不能想象任何这一类的事情。不仅宗教导师,而且教育者,都假设在人类心理植入一些以前不存在的是可能的。暗示与影响的力量是一项事实;甚至最现代的行为主义者也在这一象限预期有意义深远的结果。关于心理复杂建构的观念通过许多广为传播的信念表达为原始形态——例如,被鬼魂附体,祖先精灵的轮回,灵魂的迁移,等等。

以上所述意味深远的猜测,我称之为荣格的“灵学猜测”。现代的评论日益支持荣格的这一猜测。首先是2020年诺贝尔奖物理学家彭罗斯晚年与合作者联名发表的数学模型(Roger Penrose and Stuart Hameroff et. al.,2017,《Consciousness and the Universe --- Quantum Physics, Evolution, Brain and Mind》,标题可译为:意识与宇宙——量子物理学,演化,脑与心智,4th ed.,第1章,“Consciousness in the Universe: Neuroscience, Quantum Space-Time Geometry and Orch OR Theory”),根据这一模型,彭罗斯在2018年世界“意识”大会做主题发言时宣称“意识存在于物质之前”。根据我的解读,彭罗斯的“宇宙论”数学模型结合了量子理论与广义相对论,所谓“意识存在于物质之前”,是因为物质只能在“大爆炸”之后形成而意识存在于大爆炸之前。彭罗斯的思路之外,还有若干学术领袖分别提出了自己的思路。Shelli Renée Joye,2020,《The Electromagnetic Brain》(电磁的脑)概述了关于“意识的非局部性”假设的十二种理论(包括彭罗斯的理论)并提出了检验方法。

此外,对荣格“灵学猜测”的最有力支持来自“濒死经验”的研究领域。例如,有三次濒死经验的日本天文学者木内鹤彦在2014年著作《濒死经验》里认为,意识在身体死亡之后或迟或早将融入“巨大意识体”(其实就是荣格所说的“集体无意识”)。Luis Minero,2012,《Demystifying the Out-Of-Body Experience --- A Practical Manual for Exploration and Personal Evolution》(离体经验的去神秘化——探索与个人演化的实践手册),概述了包括他自己的经验在内的许多意识离体技巧,根据这些技巧,他认为每一个人,只要在实践中找到适合自己的技巧,就可随时诱致“意识离体”。

学院派心理学家的研究报告,可参阅:Frederick Aardema,2012,《Explorations in Consciousness --- A New Approach to Out-of-Body Experiences》(意识之探索——关于离体经验的一种新思路)。作者是加拿大蒙特利尔大学研究人员,为他这本著作作序的是蒙特利尔大学心理学研究教授。沿着这一思路,每一个人都可在死亡降临之前就熟悉“死亡”,从而极大缓解了由于“陌生”而有的恐惧感,也许还可缓解由于留恋“此生”而有的恐惧感。

不必通过死亡就可主动感受意识离体,这是一个非常诱人的思路。这一思路在巴西已发展成为包括数万名志愿者在内的“心理投射”学派,这一学派的创始人,Waldo Vieira(1932-2015)汇集了一部大型参考书,2016年第2版:《Projectiology --- A Panorama of Experiences of the Consciousness Outside the Human Body》 (心理投射学——人类身体之外的意识之经验的全景描述)2nd ed。根据这一学派的一个俱乐部最新发布的视频(The Bridge Book Club 2022 - Projectiology #19),经过一段时间的自我训练,意识即将离体时,可感受到身体重量的减轻和身体范围的扩展。

借助于来自不同文化传统的意识离体经验,我们既能批判地理解诸如《西藏度亡经》或《埃及亡灵书》这样的死亡学(Thanatology)专著,又能批判地理解海德格尔很可能从道家思想或佛家思想受启发而建构的“此在”概念(参阅维基百科“Dasein”词条的相关讨论)。并且在这样两方面的批判性理解基础上,我们可能亲身体会“涅槃”境界之“不生不灭”为何是“了却生死”的终极方案。

身体死亡之后,个体意识融入集体无意识,并继续保持某种“个体性”。融入集体无意识的无数个体意识,它们相互之间不再有身体的隔离。在这一意义上,它们是“同体的”,也因此有了许多“超时空感应”的现象。研究这类现象的学科,被称为“parapsychology”——通常译为“灵学”,却很难传达上述的全部内涵。荣格多次推测,佛教和基督教,乃至一切宗教的终极信念都源于个体意识融入集体无意识的经验——通常称为“神秘体验”。

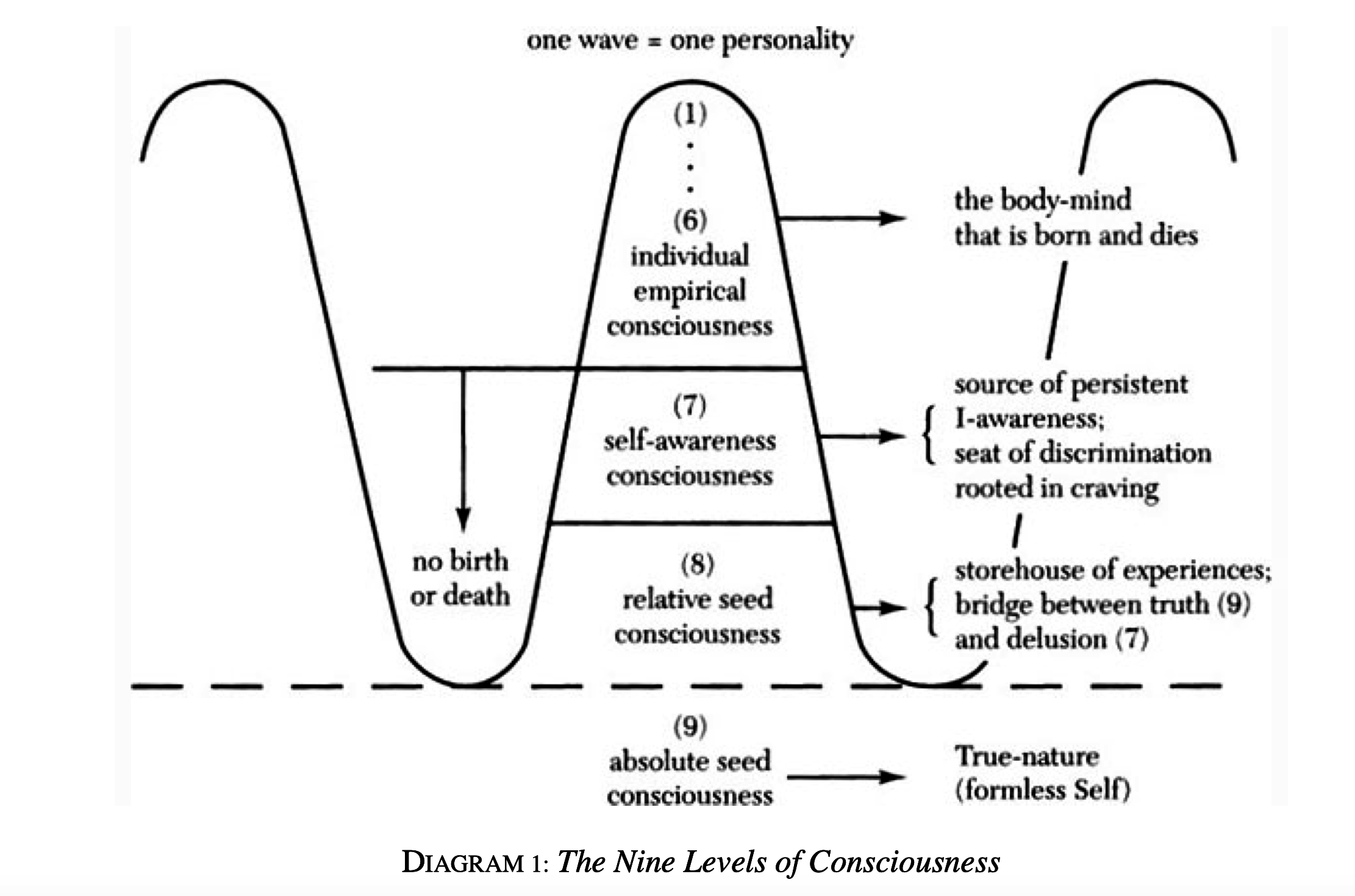

图3. 截图取自:Philip Kapleau,1998,《The Zen of Living and Dying --- A Practical and Spiritual Guide》(标题可译为:生与死的禅——实践与精神的指导),示意图1:意识的九个层级。此处第七层级的英文标识是“自我觉察的意识”(末那识),第八层级的英文标识是“意识的相对种子”(阿赖耶识),第九识的英文标识是“意识的绝对种子”(参阅牟宗三《中国哲学史十九讲》第十四讲:《大乘起信论》之“一心开二门”)。注意,第九层级向右方演化进入“真相”——括号内的英文是:无形的原我。

此处应当顺便提及,悲悯是超时空的,同情是限定在具体时空里的。这是因为,前者与个体意识的同体性密切相关而后者与个体意识嵌入的身体密切相关。参阅:Tania Singer et. al.,2020,“differential benefits of mental training types for attention, compassion, and theory of mind”《Cognition》,vol. 194,104039。与“同情”相关的脑科学研究领域,辛格是权威人物。她晚近十年研究“正念”修行与“悲悯”并主持推广训练项目,成就斐然。

另一应当顺便提及的,是“阿赖耶识”和“无生无灭”与荣格的“集体无意识”学说之间的关系,如图3所示,“无形的原我”相当于融入集体无意识之后仍保持某种个体性的意识。三篇相关文献的索引:Philip Kapleau,2000,《Zen --- Merging of East and West》(标题可译为:“禅——融汇东方与西方”)以及他关于意识的九个层次(眼、耳、鼻、舌、身、意、末那识、阿赖耶识、无生无灭)的讨论:Philip Kapleau,1998,《The Zen of Living and Dying --- A Practical and Spiritual Guide》(标题可译为:生与死的禅——实践与精神的指导);牟宗三,1983,《中国哲学十九讲》第十四讲(《大乘起信论》之“一心开二门”)和第十五讲(佛教中圆教的意义)。虽然,牟宗三只是提出了问题而未求解问题。我推测,哥德尔“不可能性”定理之后,牟宗三所说的“圆教”,难以自圆其说。

由于个体意识在融入集体无意识之后仍可保持某种个体性,因而在已融入集体无意识的无数个体意识之间仍可保持某种差异性。又由于集体无意识是超时空的,这种差异性可在任何时空涌现到意识里,最常见于梦境里。不过,涌现在梦境里的无意识,往往混杂着个体无意识。就我自己的经验而言,根据重要性感受的个体性和集体性,很容易区分出现在梦境里的个体无意识的象征符号与集体无意识的象征符号。所以,梦境分析的关键是象征符号而不是象征符号的类型。(未完待续)

0

推荐

京公网安备 11010502034662号

京公网安备 11010502034662号